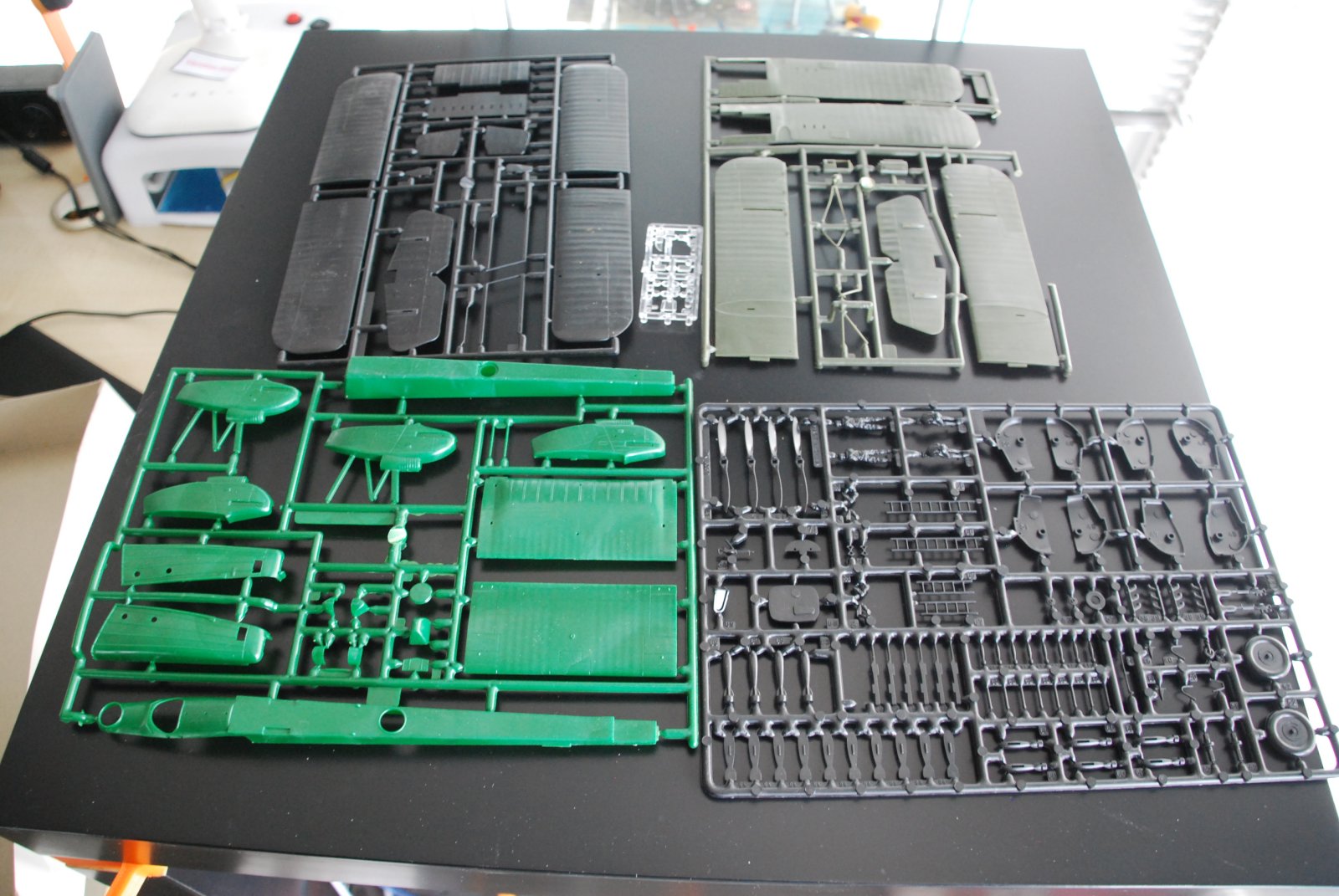

Manufacturer: Matchbox

Scale: 1/72

Additional parts: 3D printed parts

Model build: Now 2020 - Feb 2021

Manufacturer: Matchbox

Scale: 1/72

Additional parts: 3D printed parts

Model build: Now 2020 - Feb 2021

October 1939, North Sea

Oberleutnant Franz Schmidt gripped the control yoke of his Do 23/G-2, the thrum of the BMW IX engines a constant thrumming counterpoint to the icy wind whipping through the cockpit. Below, the choppy grey expanse of the North Sea stretched as far as the eye could see. Franz wasn't supposed to be here. The Do 23, once a proud bomber, was now relegated to training duty, a relic overshadowed by the sleek Do 17s and Ju 86s roaring off the production lines. Yet, here he was, leading a flight of three on a patrol exercise – a far cry from the glory he craved.

Suddenly, a dark dot caught Franz's eye. "Sergeant Müller! Plot these coordinates!" he barked. Müller, a young recruit with eyes wide with nervous excitement, leaned over his map, tracing a course. "Looks like a surfaced vessel, Herr Oberleutnant," he stammered.

Franz peered through the gunner's sight. A dark shape bobbed on the waves, unmistakable – a submarine. The rising sun glinted off its hull, revealing the markings of a British S-class sub. A jolt of adrenaline surged through Franz. This was no training exercise anymore.

"Enemy vessel sighted!" he bellowed into the radio. "British S-class submarine, current location…" He rattled off the coordinates, heart pounding. There was a tense silence, then a crackle of static. "Prepare for engagement," a voice rasped in his ear. "This is your only chance, Schmidt. Make it count."

Franz wasn't sure what that meant, but the unspoken threat spurred him on. He tightened his grip on the yoke and banked the Dornier, urging the aging machine towards the unsuspecting sub. The other two Do 23s fell in line behind him, their twin machine guns glinting ominously in the sun.

The submarine scrambled. Anti-aircraft guns swivelled towards the approaching Dorniers, spitting defiance. Tracers arced through the air, a deadly ballet narrowly missed. Franz gritted his teeth, pushing the Do 23 to its limits. The outdated bomber wasn't built for speed, but every extra knot closed the distance a fraction faster.

With a roar, they were upon the sub. Franz opened fire, unleashing a torrent of lead. The other Dorniers joined the fray, their machine guns hammering the exposed deck. The sub captain, desperate, ordered a crash dive. But it was too late. The hail of bullets found its mark, tearing into vital equipment. Smoke billowed from the conning tower as the sub sputtered, its dive halted.

A tense silence followed the cacophony of gunfire. Then, a white flag emerged from the crippled sub, fluttering defiantly against the grey sky. Disbelief washed over Franz. An outdated bomber, a training mission – and they'd forced a surrender. He radioed the news, a thrill coursing through him.

It wasn't the glorious dogfight he'd envisioned, but in that moment, as the old Dornier circled the vanquished sub waiting for backup, Franz knew he'd made his mark. The Do 23, the underdog, had roared one last time.

By the dawn of the 1930s, the Luftwaffe’s rebirth was still a secret ambition rather than a reality, but Germany’s aircraft industry was already preparing for it. Among the pioneers was Dornier Flugzeugwerke, which began developing what would become the Reich’s first post–World War I heavy bomber — the Do 11. Conceived in secrecy and under civilian cover, the Do 11 marked the first step in Germany’s slow return to strategic air power.

However, the aircraft’s early promise faded quickly. The Do 11 suffered from structural weaknesses, poor handling, and underpowered engines. In a continuous effort to salvage the design, Dornier introduced a series of improvements — first the Do 13, and then the Do 23, which entered production in 1934. Despite its ungainly appearance and limited performance, the Do 23 served as a vital stepping stone toward more capable bombers such as the Do 17, He 111, and Ju 86.

By 1936, with the new generation of fast, all-metal bombers taking over, the Do 23 was already obsolete. Yet Dornier engineers refused to let the design die. Believing the aircraft could still serve as a reliable long-range platform, they undertook one final modernization effort — the Do 23/G-2.

This last variant received numerous refinements: a cleaner, more aerodynamic fuselage, reinforced wings, and most importantly, new BMW IX engines, each producing 950 horsepower compared to the 750 of the earlier BMW VI. These upgrades pushed the top speed from 260 km/h to nearly 295 km/h — still no match for the sleek new twin-engine bombers, but enough to justify limited production. Somewhere between 20 and 30 examples were completed by late 1936, serving briefly with bomber squadrons before being replaced and reassigned to training and auxiliary roles.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the aging Do 23s were largely forgotten relics of an earlier era. Most were relegated to training schools, while a handful were converted for experimental purposes — including chemical dispersal tests and anti-mine operations with large degaussing rings fitted beneath their fuselages.

But the aircraft’s final chapter came in October 1939, during a routine navigation exercise over the North Sea — an incident that would become the Do 23’s only recorded combat “victory.”

A formation of three Do 23/G-2s from a northern training squadron took off from an airfield near Hamburg, flying a triangular route over Helgoland Bight. About 50 miles northwest of the island, they spotted a submarine on the surface — a British S-class boat that had been forced to surface due to mechanical failure. The bombers, unarmed with bombs but carrying full belts of machine-gun ammunition, immediately attacked. Their 7.92-mm MGs stitched the water around the submarine, causing no real damage but terrifying its exposed crew.

Out of ammunition and unable to dive, the British commander ordered his men to raise a white flag — surrendering to the three lumbering bombers circling overhead. The lead aircraft radioed the nearby Helgoland naval base, which hastily dispatched an elderly World War I–era torpedo boat to take the surrender. For nearly two hours, the three Dornier crews circled the crippled submarine like guardian vultures until the German ship arrived and escorted the captured sub and its crew back to port.

The “Helgoland Incident,” as it became known among Dornier test pilots, was never widely publicized, but it remains one of the strangest episodes of the early war — a slow, obsolete bomber design from the early 1930s claiming the surrender of a modern Royal Navy submarine.

After 1940, the last Do 23s were scrapped or cannibalized for parts, their brief moment of accidental glory already fading into obscurity. Yet in that one bizarre encounter over the grey waters of the North Sea, the Dornier Do 23/G-2 earned a peculiar place in aviation history — the only aircraft ever to capture an enemy submarine without dropping a single bomb.

The model is based on the 1/72 scale Matchbox Handley Page Heyford kit. It was mostly built OOB, modifications were a single, 3D printed tail (original taken from a FW-200), and removal of the lower wing. Instead, a new landing gear was 3D printed. Also, the antenna was added form the spare part box.

The model was painted with Revell Aqua Color in a mid 1930s camo scheme. Decals were taken from various models in the spare part box.