Manufacturer: PM-Model

Scale: 1/72

Additional parts: none

Model build: Dec 2015-Jan 2016

Manufacturer: PM-Model

Scale: 1/72

Additional parts: none

Model build: Dec 2015-Jan 2016

August 10th, 1945. The Pacific sweltered under a relentless sun. On a hidden airstrip carved into a volcanic mountain on a forgotten Japanese island, Captain Hiro Tanaka paced beneath the sleek, orange form of the Ki-229. Christened "Koumori no Tsubasa," or Bat Wing, it was a technological marvel - Japan's last hope against the relentless American B-29 bombers.

Tanaka wasn't supposed to be the pilot. The Ki-229 was slated for a test flight by a more senior officer, a prelude to a desperate kamikaze mission. But fate, like the B-29s, was unpredictable. News had crackled over the radio the previous night - the Emperor planned to surrender. Despair hung heavy in the air, thick enough to choke on.

Then, a transmission. A scrambled message from a rogue Imperial faction, a splinter cell who refused to accept defeat. They offered a plan, a final gamble. A prototype American bomber, the B-36, was due to fly over the island that very night, a recon mission before a full-scale invasion. They proposed Tanaka steal the Ki-229, use its untested jet engines and unorthodox design to evade radar, and destroy the B-36.

Tanaka's heart hammered against his ribs. It was a suicide mission, a one-way flight into the unknown. But it was a chance to strike back, a sliver of defiance in the face of annihilation. With a steely glint in his eyes, Tanaka climbed into the cockpit.

The Ki-229 roared to life, a guttural beast awakening. He taxied down the makeshift runway, the volcanic ash spitting at the undercarriage. Taking a deep breath, Tanaka steered the Bat Wing off the cliff's edge. The world tilted, the runway a receding memory.

The night sky was a canvas of inky black, dotted with a million indifferent stars. Tanaka pushed the experimental jet engine, the Ki-229 slicing through the air like a phantom. The radar warning light remained stubbornly dark - the plane's unique design, a blend of wood and composite materials, seemed to confuse American technology.

Then, on the horizon, a flicker of light - the B-36, a lumbering mechanical leviathan. Tanaka pushed the Ki-229 to its limits, the sleek black form weaving between the B-36's escort fighters. The sky erupted in a ballet of tracers and explosions, but the Bat Wing, a ghost in the machine, remained untouched.

Tanaka lined up his shot. The B-36 loomed large, a symbol of American might. With a squeeze of the trigger, his cannons roared. The B-36 shuddered, a fireball blossoming in the night. It spun out of control, a flaming harbinger of defiance in the face of surrender.

Tanaka knew he wouldn't make it back. Fuel was low, and American fighters, alerted by the fiery spectacle, were closing in. But as the Ki-229 plunged towards the unforgiving ocean, a flicker of a smile touched Tanaka's lips. The Bat Wing had flown, a testament to Japanese ingenuity, a defiant roar in the face of defeat.

Nakajima Ki-229 コウモリの翼 (“Bat-Wing”) – Japan’s Flying Wing Jet Fighter

In the closing months of the Second World War, Japan’s aircraft industry was in a race against time. Facing relentless Allied bombing and dwindling resources, Japanese engineers looked to their German allies for technological inspiration. By 1944, the exchange of aeronautical data between the Axis powers had produced remarkable results: the Nakajima Kikka, clearly influenced by the Messerschmitt Me 262; the Nakajima Ki-201, an almost direct adaptation of the same; and the Mitsubishi J8M Shūsui, a licensed version of the rocket-powered Me 163 Komet.

Among the lesser-known—but arguably most ambitious—of these German-inspired projects was the Nakajima Ki-229 コウモリの翼 (Kōmori no Tsubasa), or “Bat-Wing.” Based closely on the Horten Ho IX / Gotha Go 229, the Ki-229 was Japan’s bold attempt to build a flying-wing jet interceptor. The aircraft promised exceptional aerodynamic efficiency, high speed, and a reduced radar profile—concepts far ahead of their time.

Work on the Ki-229 began in December 1944, following the arrival of partial blueprints and aerodynamic data transmitted from Germany via submarine. Nakajima’s engineers, led by Chief Designer Saburō Koyama, modified the original Horten layout to accommodate locally available components. The Ki-229 was to be powered by two Ishikawajima Ne-130 turbojets, license-built adaptations of the BMW 003 engine, and armed with two 30 mm Ho-155 cannons in the wing roots.

Construction took place under extremely difficult wartime conditions at Nakajima’s Ota plant. Material shortages, Allied air raids, and the loss of experienced engineers slowed progress to a crawl. Still, by July 1945, the first prototype—made of a combination of steel tubing and wood—was 85% complete. Initial ground testing of the engines began in early August, with the first flight scheduled for August 15, 1945 at Matsudo Airfield.

Fate intervened. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. The Ki-229 never left the ground. American occupation forces soon discovered the incomplete prototype, along with partial construction jigs and flight data, hidden in a hangar northeast of Tokyo.

The unusual swept flying wing caught the attention of U.S. intelligence teams, who arranged for the airframe and design documents to be shipped to the United States under Operation Lusty. Although the Ki-229 itself was never completed or tested, its aerodynamic research—along with that of the German Horten project—would later influence early American flying wing experiments, such as the Northrop YB-49.

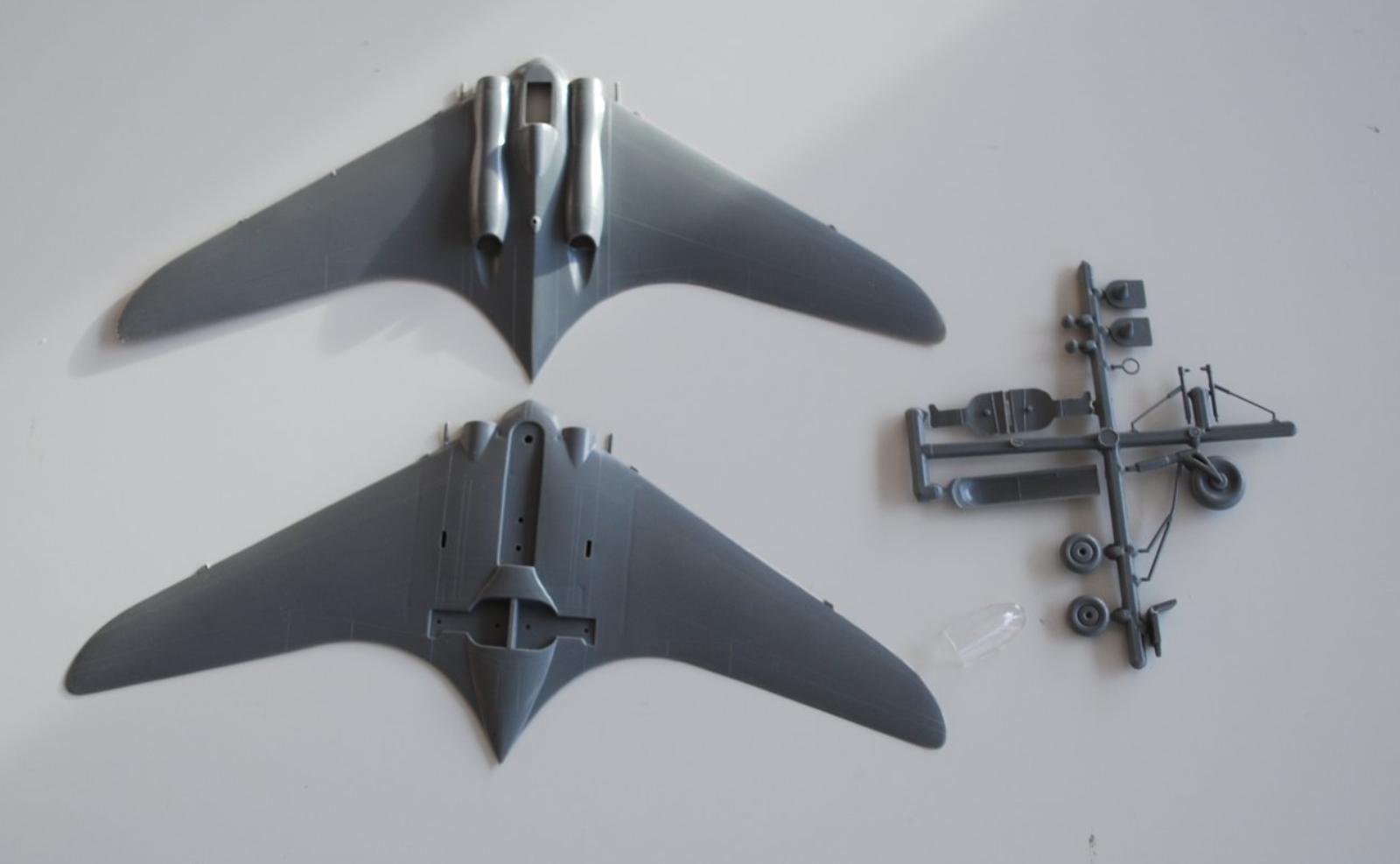

The model shows the Nakajima Ki-229 in its prototype colors on the days of its planned maiden flight in August 1945.

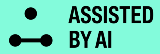

The model was made from a PM-Model kit which consited of less than 20 parts. Like most of the kist of this Turkish manufacturer. Airbrushed with Revell Aqua Color it was build OOB, just the cannons were removed. Decals are form a Mitsubishi Zero kit.